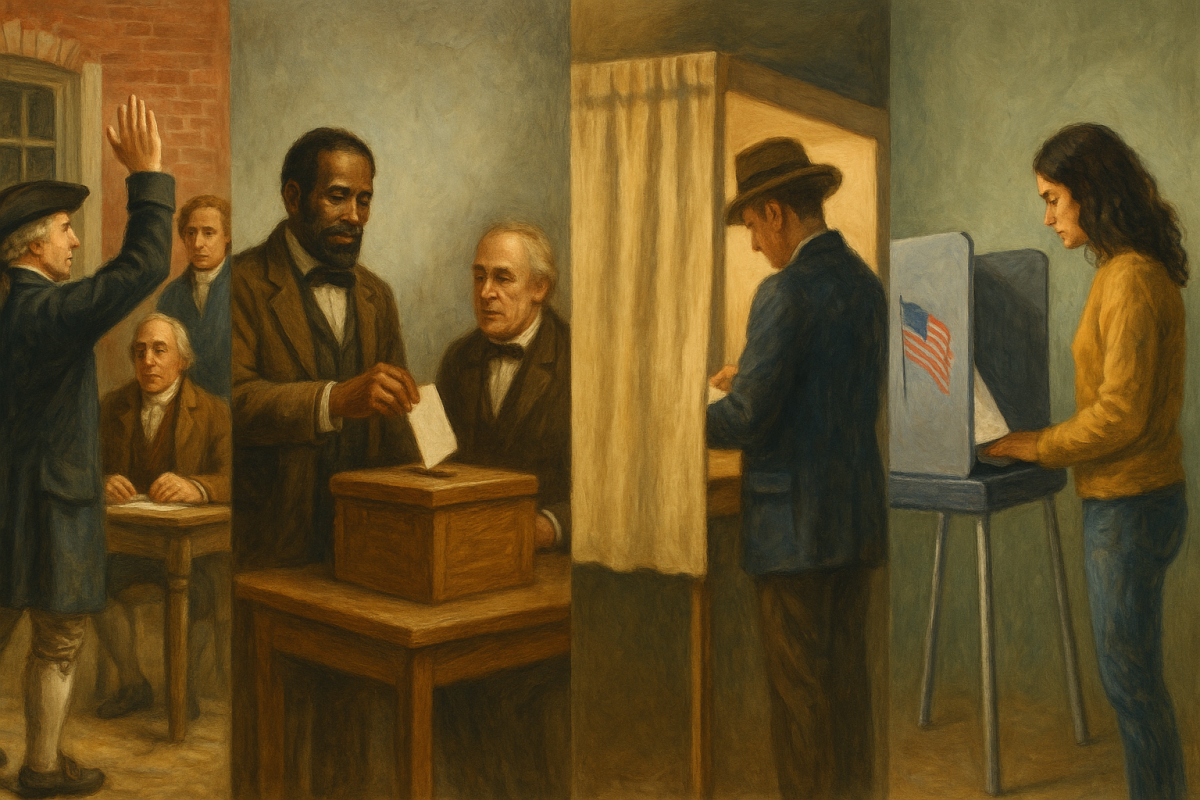

When we think about voting today, we picture a private act—stepping into a booth, filling out a ballot, and submitting it in secret. But in the early days of America, voting looked and felt very different.

In colonial America and the early Republic, many elections were conducted viva voce—Latin for “by voice.” Eligible voters (mostly white, male property owners) would stand before their community and loudly declare their choice. Everyone—from neighbors to employers to political leaders—knew exactly how you voted. At the time, this was seen as a mark of civic virtue and accountability. If you were going to cast a vote, you should have the courage to stand by it publicly.

But there were major flaws. Public voting opened the door to intimidation, bribery, and even violence. Imagine a landowner telling his farm workers how to vote, or a tavern owner “rewarding” patrons who voted for his candidate of choice. With no privacy, the pressure to conform was overwhelming.

By the mid-1800s, reformers began pushing for a better system. The secret ballot, sometimes called the “Australian ballot,” was introduced in the United States in the late 19th century. This allowed citizens to cast votes privately, protecting individual choice while still ensuring fairness and accountability. Over the decades, further reforms expanded who could vote—abolishing property requirements, extending suffrage to African American men (15th Amendment), to women (19th Amendment), lowering the voting age to 18 (26th Amendment), and strengthening protections against racial discrimination (Voting Rights Act of 1965).

Today, voting can take many forms—in-person at polling places, by mail, through early voting, or with modern machines. But the journey from public voice votes to private ballots wasn’t just about technology. It was about leadership, fairness, and the fight to include more voices in the democratic process.

That same journey offers important lessons for today’s student leaders, who are constantly building systems of decision-making in their schools.

Quick Timeline of Voting in America

1600s–1700s: Viva Voce voting (by voice) in many colonies. Only white male property owners could vote

Early 1800s: Property requirements gradually dropped; more white men gained the right to vote.

1870: 15th Amendment – African American men granted the right to vote (though many barriers remained).

Late 1800s: “Australian ballot” (secret ballot) spreads across the U.S., protecting voter privacy.

1920: 19th Amendment – Women gain the right to vote.

1965: Voting Rights Act outlaws discriminatory practices like literacy tests and poll taxes.

1971: 26th Amendment – Voting age lowered to 18.

Today: Voting takes many forms—mail-in ballots, early voting, electronic machines—with ongoing debates about access, security, and participation.

Key Lessons for Leadership Students

Fairness and Privacy Matter

Early voice voting showed how public pressure can distort decision-making. Leaders must design systems that protect individual voices while ensuring fairness.

Inclusion is a Leadership Responsibility

Voting rights expanded only when people noticed who was left out and pushed for change. Leadership students should ask: Who’s not at the table? How can I bring them in?

Balancing Transparency and Confidentiality

Leadership requires both openness and discretion. Students can learn when to make decisions visible and when privacy builds trust.

Responsibility and Civic Virtue

Voting has always been framed as a civic duty. Leadership students can reflect on their responsibility to act for the good of the group, not just themselves.

Reform Comes Through Advocacy

From suffragists to civil rights leaders, voting reforms happened because people identified injustices and fought to change them. Leadership students should see advocacy as part of their role.

Change Management is Hard Work

Switching from voice votes to secret ballots required cultural and logistical adjustments. Student leaders can learn that introducing new systems takes time, planning, and persistence.

Classroom Activities and Lessons

Election Simulation

Run two mock elections in class: one where students vote out loud (viva voce), and one with secret ballots. Then discuss: Did you feel pressured? Did you change your vote? Which system felt more fair?

Eligibility Timeline

Have students research who was allowed to vote in different eras (colonial times, post-Civil War, after women’s suffrage, after the Voting Rights Act). Create a visual timeline of how voting expanded.

Reformers in Action

Assign groups to research key voting rights advocates (Susan B. Anthony, Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, etc.) and present how they led change.

Design a School Election System

Challenge students to design the “perfect” election for ASB, clubs, or class officers. They must consider: fairness, privacy, accessibility, and cost.

Ethics Reflection

Pose a discussion: When is transparency good? When is privacy more important? Relating this to leadership roles (budget, discipline, recognition) makes it real.

Modern Challenges Debate

Introduce today’s voting issues—like turnout, misinformation, and access. Ask: How do these challenges mirror what you see in school elections? What can leaders do about it?

Closing Thought

The journey from public voice votes to today’s private ballots is a story of evolving leadership—recognizing problems, including more voices, and building systems that inspire trust. By learning from America’s voting history, student leaders can reflect on their own responsibilities: creating fair opportunities, including all voices, and ensuring that their leadership leaves a legacy of equity and trust.